January 06, 2014

Manfred’s Life (As I Knew It)

This is by my cousin Nora Hanke, who's a pediatrician, rescues animals, grows her own kale and has a huge solar array to help power her house. I.e., she does everything right. Also, she once told me about infected abscesses in such detail that I fainted.

Manfred’s Life (As I Knew It)

Manfred came into my life in September, 2000 when I saw a skinny little kitten run under dumpster at the Southampton Transfer Station. I asked a worker about him and was told, “Oh, he’s been hanging around here for a couple weeks. Someone dumped him off. It happens all the time. He is going to starve to death.”

“No way,” I thought.

I started visiting the site twice a day – even though it is only open 3 days a week. It was a cold and wet September. I made a little shelter for the cat and left food and drink. Sometimes I had to hide from patrolling police.

Once I found him sleeping in the shelter. He jumped up, stared at me, and then ran off.

After 2 weeks, he still wouldn't trust me. So I borrowed a Have a Heart trap and set it to catch him. It worked right away, to Al’s amazement (he didn’t think I could set it properly).

The little cat came home, and because I thought my other cats Reto and Bebe would need to adjust to him slowly, he went into the basement. Unfortunately, there is a lot of stuff down there and he disappeared right away. The outlet tube of the dryer had gotten disconnected from the wall, leaving an opening the kitten could use to escape. So I picked up the tube to reconnect it. It was strangely heavy. Then I noticed a little orange tail inside. He was inside the tube and I couldn’t get him out. I had to cut the tube open. Then, he ran under the woodpile.

Once Reto came downstairs and the kitten heard him. Suddenly, a loud, vibrating purr came from the woodpile! But he still wouldn't come out.

I started to spend part of every night on the floor next to the woodpile, in a sleeping bag. A trail of dry food led from the woodpile to the sleeping bag and he followed it into the sleeping bag. But as soon as I moved he would run back to the woodpile.

After another two weeks of this, I finally just grabbed him, sat him on my lap and stroked him. That was an important turning point. He felt more secure, and started to live upstairs.

Reto accepted him, just as Bebe had accepted Reto. But Bebe was freaked out about the new cat. One morning she attacked Manfred. That day, after less than a year with me, Bebe disappeared and I never saw or heard of her again.

Reto and Manfred became great friends. At first, Reto was in charge. But as Manfred became fully grown, he started to bully Reto a little – when they were inside. They were still buddies, and played and slept together. But when they went outside, Reto came into his own as the Great Grey Hunter, and Manfred became the meeker of the two.

Some winters, I shoveled circuits through the snow in the back yard and Reto and Manfred ran around in them after each other.

Aside from his loud purr, Manfred didn’t make sounds very often. It was always surprising when he did vocalize. But he did sometime like to get crazy. There was a special sound he made when he was like that. He would make the sound at an unexpected moment and then jump up and run around. He liked to run upstairs and dive into the (empty) guest bathtub and hide.

By 2008, Manfred and Reto’s outside time had become restricted, for their safety and the safety of wildlife. They were allowed out for a few hours at a time, at most, and only during daylight, when I was home. One evening in October, Reto wouldn’t come in when I called, but Manfred did. I went outside again and again and Reto didn’t want to come. It became dark. Around 9 o’clock, Manfred suddenly sat up on my lap. I didn’t know what had bothered him. But a few minutes later, a neighbor called about Reto. I went outside, and found him dead. Manfred must have heard Reto when the car hit him.

When Reto was gone, he didn’t have a cat friend to share the bathtub game. There was just me to run after Manfred and rub his belly and tell him how wild he was.

For a month or so, Manfred had no feline companion. In November, a staff member had a predicament with her cat and he came to live with us for a few weeks. The cat was young and wanted to play with Manfred. But Manfred was shy and didn’t feel comfortable with the new cat. He kept running away. The other cat bit Manfred on his fleeing bottom and Manfred developed an abscess within hours. He required surgery and a drain.

The foster cat was evicted but in January, 2009 I adopted a new cat from the Springfield Humane Society, hoping they would become friends.

Unfortunately, they never hit it off. Jesper is a confident and large framed cat. Manfred was always fearful of Jesper, and Jesper took advantage of that.

That April, driving to the Southampton Transfer Station again near a down-at-its-heels dairy farm, I saw a cat lying in grass near the road. There was something wrong with his rear legs. Dr. Shelburne examined and treated him. She reported that he had broken bones but could heal with confinement.

So Charles, a wild “barn cat” came home and went into a dog “crate” on my desk by the window. Manfred didn’t seem too interested but Jesper took to hanging out by the cage. Once Charles was healed enough to leave the cage, he became best buddies with Jesper.

Charles sometimes lay next to Manfred, too, but I don’t think they groomed each other.

Manfred wasn’t afraid of Charles, but he seemed indifferent to him.

So, with two new cats Manfred remained on the outside, still with no cat buddy after Reto’s untimely death.

Instead, Manfred and I became closer. He helped me in the garden. Whenever I had a lap and he spotted that, he jumped up and settled right down. Even if I was on the throne.

He greeted me every day when I came home, and always wanted to smell my breath first thing. If I had just eaten chocolate, he acted very interested. (But I didn't think cats were allowed chocolate, so I didn't let him have any.)

Outside, Manfred liked to run up to trees and sharpen his claws on them. In the good old days, that was a frolic he has shared with Reto.

Manfred never pursued a bird, and though he caught frogs sometimes, I don’t know that he ever killed one.

Over the 2-3 years after Jesper arrived, he became – despite having a serious illness – more and more aggressive with Manfred. I had to be alert and try to intervene in time. Several times I failed, and Manfred was bitten by Jesper. There were multiple occasions when he needed antibiotics.

Jesper became confined to the study when I went away during the day, only coming out when I was home and could supervise.

When Jesper was out, Manfred became alert and anxious whenever he sighted him. He was often pursued by Jesper, and Jesper would atttack Manfred right in front of me.

When I was lying down on the sofa to read, Manfred no longer was able to lie on my chest, because of Jesper. But he sometimes hid under the blanket on me to lie on my legs.

By some time in late 2012 or in 2013, I had to take more consistent protective measures, and started closing the bedroom door at night (Manfred staying inside the bedroom with me). When Manfred could relax, he still had his power purr.

A routine checkup in the winter of 2012-’13 revealed Manfred had some weight loss, but also a bad tooth that could be the cause. I thought he might regain the weight after his mouth was fixed. But he gradually lost more weight over the subsequent months.

In retrospect, I have often wondered whether the stress from Jesper’s harassment caused or hastened Manfred’s decline.

Manfred always liked to chew on pens, and play with rubber bands. So I had to hide those kinds of things. But in June of 2013 there was a crisis: the vet thought a rubber band was blocking his stomach. Manfred was urgently referred to the Boston emergency vet hospital. He spent most of the weekend in the hospital, and on conclusion was diagnosed with no foreign body blockage but instead either food allergy or bowel lymphoma. They wanted him to undergo endoscopies and biopsies but I thought the financial and emotional costs would be too great for both of us.

Empirically, he was prescribed several symptomatic medications, and various hypoallergenic veterinary diets, none of which did he like.

By August, when he wasn’t improving, he was seen by another specialist vet in Deerfield. She concurred with the diagnoses and again recommended the procedures and biopsies.

I felt the same way about those suggestions, so we just did some more dietary tinkering. The theory was that his weight loss might be due more to not liking the food.

By the fall, after having tried more than 6 kinds of new canned food and 3 kinds of new dry food, he was continuing to gradually decline in weight and vigor. Dr. Shelburne supported treating him as if he had lymphoma, with a trial of daily steroid shots.

Manfred seemed to respond with an increase in appetite but seemed to decline whenever I tried to back off on the dose.

Manfred was always a grazer. In the days when it was just Manfred and Reto, there was cat food out all the time and they came and went, nibbling as they felt hungry. But Jesper and Charles are huge eaters, and will eat anything accessible. So Manfred could only eat when I was home, or when he was separated from the other 2 cats. But confining him for hours so he could nibble as he wanted seemed a poor trade off from his usual freedoms, so he was eating only twice a day.

In December, Manfred developed a habit of pawing me gently every hour or two overnight. That action used to mean, “raise the covers, I want to snuggle.” But it now meant he wanted to be fed again. Of course, I was thrilled if he would eat. Because historically Manfred had been prone to vomiting, I did not want to give him a large amount at any one time. So he would get ¼ of a can of cat food repeatedly overnight, whenever he asked.

Manfred turned 13 in 2013. I expected Manfred would live to a ripe old age. 19 years was in my head, somehow. But, by December, I also began to perceive that Manfred was getting sicker and might not get better. It was still hard to believe that he wouldn’t be around for years to come.

I changed my plans to be home more.

There started to be some days when Manfred wasn’t feeling well enough to come to the door to greet me, when I got home from work.

Shortly before Christmas, one night not only would Manfred not eat dinner, but he also vomited up all the dry food he had consumed almost 12 hours earlier.

After that day, Manfred only ate wet food, made wetter with added warm water.

But, I still hoped that Dr. Shelburne was right that he might last even a year with the right dose of steroid shots.

He didn’t vomit again, and continued to ask for more food several times overnight. Yet, he was getting thinner and weaker, and had a markedly bony spine and hips.

Manfred was already having trouble running away from Jesper and jumping onto the counters. One day in late December Manfred tried to jump onto the counter while I prepared the cats’ food, and he didn’t make it, splaying all 4 limbs out on the floor when he fell.

Another day I found sick cat weasel-like stool on the floor in my bathroom, near but not in his litterbox (located a foot or so above the floor, on the bathtub surround). He hadn’t been able to jump up to the litterbox in time. So the box went onto the floor.

A few days after Christmas, Manfred had a bad night. He was very lethargic and seemed uncomfortable. He was breathing fast. I didn’t know what was going on or how to help him. I gave him some of Jesper’s emergency pain medicine, but it didn’t help. His breathing remained fast and became noisy. I thought he was going to die. But finally he seemed a little better, and the crisis was mysteriously past.

Dr. Shelburne was away but Manfred needed to be checked, and preferably at home. I couldn’t get a house call till the afternoon of January 2nd. But the hours passed, and he got weaker. Manfred needed to be seen sooner. So, Dr. Ksiazek saw him on December 31st, in the office. She was struck by his muscle wasting but suggested no change to his routine. She couldn’t tell me how the end would come, or when. But, she did provide an emergency shot to use if Manfred became acutely breathless.

I kept the January 2 house call appointment just in case, but thought I would probably be able to cancel it that morning. Surely he would keep going for awhile longer, with good care.

On New Year’s Day, it was cold but there was no snow on the ground, and Manfred wanted to go outside. I let him and he scampered right out. But he didn’t run up to a tree to scratch the bark, or run over to one of his favorite chipmunk holes to lurk. He crouched in a cold, shady spot. I checked him to make sure he wasn’t shivering, and since he wasn’t I moved him into the sun, at least. He moved to a spot that is very close to Reto’s grave, and stayed there, facing the grave.

After a few minutes, I brought him inside again.

Manfred ate his wet food several times over New Year's Day. That seemed a good sign. But, in the evening he seemed lethargic and wouldn’t purr. That night he slept fitfully. His belly was bothering him. He woke repeatedly to get up and tried to get to the litter box. Getting up and walking were both hard and I put a second box right on the bed for him. Several times he didn’t make it to the litterbox. He was not only weak, but seemed confused. He got up and walked a little and urinated or stooled in a wrong place. I tried to be alert for his wakenings, and jump to pick him up to bring him to a box. Sometimes he took advantage of the help. Other times I seemed to just annoy him.

Once he insisted on coming under the covers. But I was worried he would urinate or stool there and I wouldn’t let him until I laid down protective covers. Then it wasn’t like normal and he didn’t want to stay there anymore.

Manfred didn’t ask for food and I was worried about his need to urinate or stool if I did feed him.

I kept listening to his breathing and his heart for a sign of how sick he was, and whether to give him pain medicine or the diuretic shot. But his breathing didn’t get as bad as he had been a few nights before, and his toe pads stayed pink. Manfred seemed uncomfortable but I didn’t know if it was nausea or bloating or something else that wasn’t really pain. He already seemed a little foggy and I didn’t want him confused and more stumbling with an opiate dose. I offered him a few of the verboten dry nibbles and he ate one.

It finally seemed that Manfred wasn’t going to get better and I couldn’t help him in any way except by taking him completely out of his misery.

As people who have gone through some of this can appreciate, the decision to end a companion’s life is painful. Studying evolution, I am struck by how similar are different living things. Birds, sea mammals, humans, cats and dogs: we all have the same basic body parts. We all think and feel, have preferences, dislikes and fears. We aren’t that different from each other.

So it has been painful deciding on vet visits, tests, medicines and then euthanasia for Manfred without being able to engage with him about his preferences. By the morning of January 2nd, I took on the responsibility of deciding for Manfred to end his life, as the most humane way to help him.

I couldn’t go to work and leave him alone until a house call in the afternoon. It was a matter of watching the clock as the vet office opening time approached. Calling the office, they were able to change the visit time to the morning. Dr. Losert, a vet who is new to me, came with one of the best techs from the practice, Kelly, a person who had seen Manfred before. They were both kind.

I tried to give Manfred comfort. His death came quickly and seemed peaceful.

Because we were home, it was easy for Jesper and Charles to see and sniff Manfred to know he was gone.

Now we three are adapting to a changed household. Jesper and Charles have the whole house to roam all day. They can even sleep with me, if they want to. (So far, they do.)

It is hard to believe Manfred is gone now, as well as Reto (1997-2008).

They are both amongst the pantheon of great cats I have known, joining Charcoal (196x-~1981), Miss Samantha Flipp (1976-199x), and Skoda (1983-1997).

—Nora Hanke

January 04, 2014

Michael Hirsh Aims at Edward Snowden, Accidentally Blows Off Own Leg

One of the most surprising things about members of the U.S political establishment is that they often don't know anything about anything. You'd think they would, in the same way you assume your doctor knows where your spleen is. But in many cases they're unfamiliar with the most basic facts about history, politics, etc.

For instance, here's Michael Hirsh of the National Journal lamenting the reporting on the NSA enabled by Edward Snowden:

So the question is, what purpose does this endless and seemingly indiscriminate exposure of American national-security secrets serve? This is most definitely not the Pentagon Papers, when the Post and the New York Times exposed the truth about a war already gone by. This is, if not quite a war, then at least a genuine present danger to Americans -- a threat that is, according to some officials, only growing more dangerous.

The Vietnam War was not "already gone by" in June, 1971 when the first excerpts of the Pentagon Papers were published. After turning himself in, Daniel Ellsberg famously said, "Wouldn't you go to prison to help end this war?" He did not say, "Wouldn't you go to prison to help expose the truth about a war already gone by?" (Also, the 1972 Democratic Party platform pledged to "end the war," which would be strange if it had already gone by.)

It is true that by the time of the publication of the Pentagon Papers, U.S. involvement in Vietnam had fallen significantly from its 1968 peak and the Nixon administration had put in motion plans to greatly reduce the use of U.S. ground troops. But by any measure it was still an enormous war. There were 250,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam at the beginning of June, 1971. And still to come was the napalming of Kim Phúc (June 8, 1972), and Nixon musing about using nuclear weapons on North Vietnam (December, 1972).

In addition, if the Vietnam War was over by 1971, that implies the Iraq War never happened at all. 2,414 U.S. troops died in Vietnam in 1971. The highest yearly death total in Iraq was 904 in 2007, and the most troops ever stationed there was 166,000.

Finally, the Pentagon Papers also revealed important information about the bombing of Cambodia. And the great majority of the 2.7 million tons of bombs we dropped there were delivered after the Pentagon Papers were published. To put this in perspective, the Allies dropped just over 2 million tons of bombs in all of World War II, which is generally seen as a notable conflict.

Of course, even if Michael Hirsh were right and U.S. involvement in Indochina had been totally over by 1971, his perspective would still be something that's the opposite of journalism: i.e., that our government's actions should only be revealed once it's too late for us to do anything about them.

P.S. I strongly counsel against taking the advice of any doctor who thinks your spleen is located in your nose.

UPDATE: After this was posted, Hirsch edited his original article to read that the Vietnam war had "already largely gone by," without acknowledging the change. However, the original "already gone by" still appears in a pull quote.

—Jon Schwarz

January 03, 2014

Snowden Accuser Gordon G. Chang Works for Think Tank Run by Notorious Liars

Gordon G. Chang, currently seen in the Daily Beast claiming Edward Snowden had "high-level contact" with Chinese officials while in Hong Kong, is a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Gatestone Institute.

That's notable because the main people who run Gatestone are John Bolton (chairman) and Amir Taheri (chairman, Gatestone Europe), two of the most flagrant liars in high level politics.

Bolton lied under oath during his confirmation hearings to be U.S. Ambassador to the UN in 2005, claiming he'd "made no effort to have discipline imposed" on a State Department analyst who refused to sign off on statements that Cuba had a biological weapons program. Bolton's denial that he'd tried to punish the analyst was contradicted by other Department staffers and documentary evidence. (Bolton also led the 2002 charge to force out José Bustani from the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Bustani was making plans to send inspectors to Iraq, which Bolton opposed because it would complicate the push for war.)

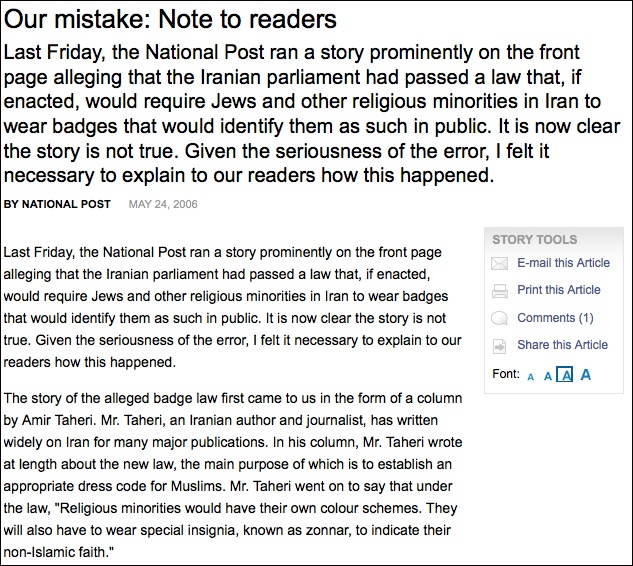

Amir Taheri made international news in 2006 by reporting that the Iranian parliament had passed a law that would require Jews to wear badges in public. This led to a gigantic, embarrassing public retraction by Canada's National Post (see below), which had pushed the story on its front page. Taheri's PR agent Eleana Benador then explained that accuracy is "a luxury"—because while Taheri may have written "one or two details that are not accurate" what mattered most was "to side with what's right."

And in terms of what's right, John Bolton says that Edward Snowden has committed treason and "should hang from an old oak tree." It's impossible to know whether Chang has simply made his entire story up, but he's certainly part of a milieu that encourages and celebrates lying to get the desired results.

***

Here's a screenshot of the National Post's retraction of the Taheri story. The Daily Beast might want to study it as a model for the future.

—Jon Schwarz